Architecture can enrich life when it honours its surroundings. That principle gleams throughout Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. The novel’s hero, Howard Roark, views nature as a source of raw material and creative inspiration, rather than a background to exploit. Below, we explore what The Fountainhead can teach about blending buildings and landscapes, with a nod to how these concepts might fit in places where architects in Limassol and best architects in Cyprus ply their craft.

The Fountainhead’s Approach

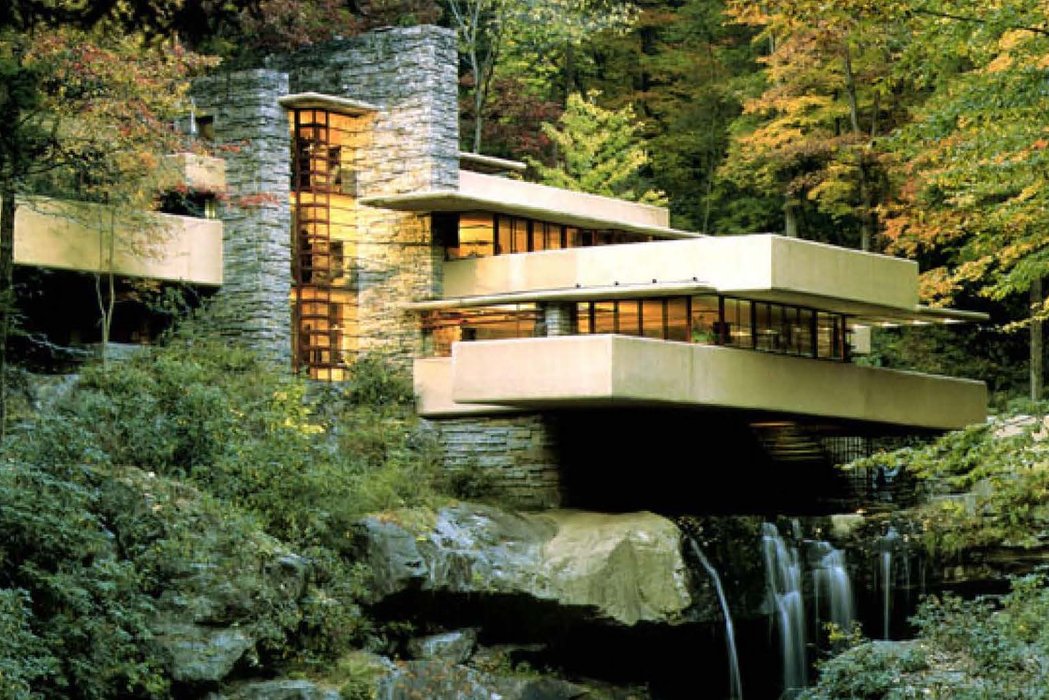

Rand’s novel opens with Roark standing on a cliff, reflecting on rock, water, and the open sky. That scene reveals her interest in nature as a building block. Roark’s designs match environment with purpose. He studies the landscape, picks materials that fit each site, and honours the truth of what nature offers. This approach underlines a truth that stands out in The Fountainhead: humans complete nature by shaping it in ways that respect its essence.

Rand contrasts Roark with second-handers who chase approval rather than truth. Those who ignore the laws of nature produce monstrosities. Their designs look forced, stuffed with borrowed styles, and disconnected from real-world conditions. That clash shows the tension between original thought and imitation.

Man as Shaper of Nature

Roark calls architecture “a conquest of nature.” Yet he means a civilising effort rather than a blind takeover. He believes that nature has no meaning without human minds at work. The outcome is a balance, where stone meets blueprint, and sunlight meets spacious rooms. In many ways, each thoughtful design acts like a handshake with the land.

This approach may inspire watchers of Mediterranean sunsets who plan a home by the sea. Picture an airy veranda, angled to welcome the breeze. Nobody wants a fortress that blocks the shore. A clear design approach respects the curve of the coast while providing what residents need. Roark’s method—observe carefully, use local stone, minimise clutter—can guide such projects, especially for those who yearn for scenic harmony. Readers seeking practical support with new designs can seek architects in Cyprus.

Harmony in Design

Rand employs motifs that highlight water, sky, and rock. They run through the novel as mirrors of Roark’s creative spark. She also celebrates spring, a season of renewal. Spring sets the stage for his biggest breakthroughs. It suggests that each architecture Cyprus project is an awakening—an emergence of fresh thinking.

In a practical sense, these ideas can spark:

- Site Analysis: Surveying terrain, soil conditions, and local climate before drawing plans.

- Purpose-Driven Materials: Selecting wood, stone, or steel that suits function, beauty, and durability.

- Respect for Space: Leaving room for greenery, breezeways, and natural light.

- Long-Term Viability: Creating buildings that age gracefully by embracing, not fighting, the surrounding topography.

That final point often shapes design in coastal regions where salt spray or steep slopes might pose a puzzle. One might recall how Roark tackled a cliff, turning it into a prime asset rather than a source of frustration.

Relevance for Architecture in Cyprus

Architectural services in Cyprus is known for its sunny coastline and striking mountain vistas. Local designers are wise to consider Rand’s emphasis on matching form to nature. Traditional village houses sometimes use stone walls, arched doors, and courtyards that invite cross-ventilation. Modern builds can expand on that tradition by including open-floor plans and large windows for natural light.

The Fountainhead’s sub-theme of man completing nature can offer guidance to those seeking architects Limassol. A well-planned roof terrace might provide a sweet spot for capturing city and sea views. Balconies that echo the lines of nearby hills can add a sense of continuity. Some folks embrace local materials, such as limestone, to ensure that a new build flows into the environment.

Final Thoughts

Ayn Rand’s philosophy may challenge or intrigue, but her belief in architecture’s power to unite with the natural world is worth pondering. Roark stands on a cliff at the start and stands on a city skyscraper at the end. The shift suggests that cityscapes do not have to clash with nature. By picking suitable materials, honouring the site, and respecting the elemental character of stone, sky, and water, architects and clients can create vibrant spaces that energise residents and visitors.

Many readers find Rand’s novel inspiring due to its portrayal of a builder who loves the earth. He shapes each structure to meet its surroundings with integrity. Roark’s approach echoes in modern-day efforts across diverse areas, such as the scenic coasts of architectural services in Cyprus. In any locale, there is room for respectful creation, solid craft, and a belief that people and the planet can work together.